Throwing Old Furniture Off High-Rise Balconies

In Johannesburg’s inner-city neighborhood of Hillbrow, some residents developed a notorious New Year’s Eve habit: literally tossing old furniture out of tower-block windows at midnight. Everything from chairs to fridges reportedly rained down on the streets as a dramatic way to “clear out the old” before January 1. Police have spent years cracking down on the custom because, unsurprisingly, it’s extremely dangerous.

Today the tradition survives mostly as a cautionary tale and occasional incident, rather than an accepted way to celebrate the new year.

Pouring Molten Lead to Read Your New Year’s Fate

For generations in Germany and parts of Central Europe, people practiced Bleigießen—“lead pouring”—on New Year’s Eve. Small pieces of lead were melted over a candle, then poured into cold water, where they hardened into bizarre shapes. Those shapes were interpreted like fortune cookies for the year ahead. Modern safety standards and EU rules effectively banned lead-based kits in 2018 because of toxic exposure risks.

Naturally, many shops stopped selling them. Today, a few families use safer wax or tin alternatives, but the traditional lead version is largely a thing of the past.

Holding a Funeral for the Old Year

Some 19th-century families and churches treated December 31 almost like a funeral. People gathered to read somber poems such as Tennyson’s “The Death of the Old Year,” listened to reflective sermons, and mourned the passing of time before midnight turned everything “new.” These events could include black clothing, candlelight, and long, serious speeches about mortality—basically the opposite of today’s glittery countdown parties.

While echoes remain in some religious services, the overtly funereal tone has mostly vanished in favor of more upbeat “New Year, new start” messaging.

Doing a Gentleman-Caller Marathon on New Year’s Day

In 19th-century New York and some other American cities, respectable young men spent New Year’s Day “calling” on as many households as possible. They dressed formally, traveled from parlor to parlor, left calling cards, exchanged brief pleasantries, and often drank a small toast at each stop. Women remained at home to receive the endless stream of visitors, sometimes tallying dozens in a single afternoon.

Newspapers even printed lists of which homes were “at home” for callers. The custom faded by the early 20th century as urban life changed and informal socializing became more common.

Sending New Year Cards Covered in Dead Birds

Victorian greeting cards for Christmas and New Year were often downright creepy by modern standards. Some popular designs featured dead birds lying in snow, bizarre anthropomorphic frogs, or unsettling insects paired with sentimental wishes for a “Happy New Year.” Scholars think the dead birds may have symbolized sacrifice or the fragility of life. To modern eyes, they look more like horror postcards.

As tastes shifted toward jolly Santas and snowy landscapes, these morbid designs quietly disappeared from seasonal stationery racks.

Refusing to Let Anything or Anyone Leave the House Before Something New Comes in First

Another New Year superstition, especially in parts of Britain, warned against letting anything—trash, ashes, even a person—leave the house before something new had come in. Families might bring in a small gift or lump of coal just after midnight before taking anything outside, so the year began with gain rather than loss. In busy modern cities, few people remember timing their garbage runs around symbolic prosperity, and the rule has mostly collapsed under the weight of convenience.

At most, it lingers as a quirky story grandparents tell, rather than a household rule anyone seriously tries to follow.

Panicking If a Woman or a Blonde Man Was First Through the Door

A particularly sexist twist on first-footing held that a woman entering first after midnight brought bad luck for the year. Some Victorian households reportedly went to absurd lengths to make sure a male neighbor or relative crossed the threshold before any female family members, even if it meant staging a midnight visit. The superstition reflected anxieties about gender and “change” in the new year.

As social attitudes shifted and the custom itself faded, this specific fear largely disappeared with it—thankfully, surviving now mainly in nostalgic anecdotes and folklore collections.

Dragging a Tall Dark Stranger In as Your First-Footer

In Scotland and parts of northern England, traditional “first-footing” meant that the first person to cross your threshold after midnight shaped your luck for the year. Ideally, you wanted a tall, dark-haired man carrying gifts like coal, bread, whisky, or a special fruit cake called black bun. Blonde or red-haired visitors, or—superstitiously—women, were sometimes seen as unlucky. In many places, first-footing has dwindled into a vague memory or occasional reenactment rather than a serious midnight strategy.

Today, a few Scottish communities still mark Hogmanay with symbolic “first-footers” or local parades, but the superstition survives mostly as lighthearted folklore and tourist-friendly tradition.

Smashing Plates on Friends’ Doorsteps for Good Luck

In Denmark, people once saved cracked or unwanted dishes throughout the year, only to smash them against friends’ front doors on New Year’s Eve. The more broken china you found piled outside your house the next morning, the more loved—and lucky—you were considered to be. While some Danes still mention the tradition, modern building rules, neighbors, and environmental concerns mean it’s rarely practiced literally anymore, surviving mostly as a charmingly chaotic legend.

Today, it’s more likely to appear in nostalgic articles and trivia lists than on anyone’s actual doorstep.

Flipping Open the Bible at Random to Tell Your Future

Victorian families sometimes practiced “Bible-dipping” on New Year’s Eve. Someone would close their eyes, open the Bible at random, and rest a finger on a verse. That line was then interpreted as a message or omen for the year ahead—whether encouragement, warning, or promise. It blended sincere faith with a hint of fortune-telling and was usually done with great seriousness.

As attitudes toward divination and scripture changed, the practice largely died out, replaced by more general devotional readings and non-mystical resolutions.

Greeting the New Year With Gunfire and Homemade Firecrackers

Across rural Europe and North America, people once welcomed the new year with literal gunfire, shooting into the air or into the ground to make as much noise as possible. Homemade firecrackers and improvised explosives were also common. Chinese New Year likewise relied on firecrackers to scare away evil spirits, but many cities have now banned them because of air pollution and safety concerns.

Today, professional fireworks displays—and strict laws about stray bullets—have largely replaced these wildly risky traditions. In many communities, they’re remembered mainly through stories and safety campaigns warning that “celebratory gunfire” is anything but harmless.

Running Outside to Bang Pots and Pans at Midnight

Before fireworks and amplified music dominated New Year’s Eve, many families simply grabbed whatever was loudest in the kitchen. Pots, pans, lids, and spoons were clanged together on porches and sidewalks at midnight to scare away evil spirits and welcome good luck. It was noisy, chaotic, and completely DIY. While children in some neighborhoods still do a mini version, large-scale pot-banging has mostly been replaced by organized fireworks shows and noise-maker packs from party stores.

New gadgets turned what was once a homemade neighborhood ritual into more of a nostalgic memory than a serious tradition.

Laying a Place at the Table for the Dead

In older Irish New Year practice, some families laid an extra place at the dinner table and left the front door unlatched to welcome the spirits of relatives who had died in the previous year. The gesture was meant to show love, hospitality, and hope for their peace in the year ahead. Today, remembrance tends to be quieter—through toasts, prayers, or visits to graves—while the literal empty place at the New Year table is far less common.

For most families, the idea now survives as a touching story about older generations rather than an active ritual.

Riding the ‘Stang’ AKA Public Humiliation as a New Year Punishment

Victorian accounts describe a rural British custom called “riding the stang,” which sometimes appeared around New Year. Neighbors who’d behaved badly—gossips, wife-beaters, or notorious drunkards—might be hoisted onto a pole or ladder and paraded through town to jeers and mockery. The victim, or their household, was expected to buy drinks for the crowd to end the humiliation. It was part rough justice, part drunken entertainment.

Unsurprisingly, the practice declined as police forces formalized and public shaming rituals fell out of favor, surviving now only as colorful footnotes in local histories.

Banging Christmas Bread on the Walls for Luck

In older Irish households, the man of the house might grab the leftover Christmas loaf on New Year’s Eve and start thumping it against doors and walls. The idea was to beat out poverty and bad spirits while inviting in plenty and good luck. Crumbs might then be swept up and eaten or fed to family members as a blessing. It’s a wonderfully odd combination of housekeeping and exorcism.

Today, the practice is rarely seen outside folklore columns and nostalgia pieces, having been replaced by more standard toasts and fireworks.

Wearing Paper Crowns From Christmas Crackers All Night

In the mid-20th century, many British and Commonwealth New Year’s Eve parties featured flimsy tissue-paper crowns left over from Christmas crackers. Guests donned the colorful little coronets and wore them for hours, pairing mock royalty with silly jokes and cheap trinkets. As party aesthetics shifted toward sequined headbands, LED glasses, and Instagram-ready outfits, the humble paper crown quietly lost ground.

You’ll still see them at some family gatherings, but they’re no longer the default uniform for ringing in January 1. These days, they feel more like retro costume pieces than essential party gear for a fresh new year.

Eating a Cow-Tongue-And-Goose Monster Pie

Some 19th-century British New Year’s feasts featured a frankly nightmare-level “raised pie.” One Victorian cookbook described a towering pastry loaded with pigeon, fowl, duck, hare, and goose, all layered around a central cow’s tongue. This meat mountain was baked in a huge crust and ceremonially sliced at New Year as an extravagant show of wealth and hospitality. It was less about flavor and more about spectacle and preservation.

Today, even the most enthusiastic foodies rarely attempt anything similar, and the tradition survives only in archival recipes and horrified retellings.

Baking Fortune-Telling Barmbrack Loaves

Ireland also had a New Year twist on fortune-telling bread. Families baked barmbrack, a dense fruit loaf, with small objects hidden inside: a coin for wealth, a ring for marriage, a rag for hard times, and so on. Whoever bit into each object was thought to receive that fate in the coming year. Sometimes the loaf was even thrown against the door first to ward off hunger, and the fragments eaten afterward.

While barmbrack still appears more at Halloween, the New Year version with baked-in omens has mostly faded from modern celebrations.

Swearing a Peacock Vow Over a Roasted Bird

Medieval legends describe knights gathering at New Year banquets to take the “Vow of the Peacock.” A roasted peacock—sometimes a pheasant—was brought in on a grand platter. Each knight placed a hand on the bird and swore to uphold chivalric ideals or complete heroic deeds in the coming year, before the bird was carved and shared.

Historians debate how often it actually happened, but the story was widely retold in later literature. Modern New Year’s resolutions are tamer—and thankfully require no decorative roast bird as a witness.

Opening the Back Door to Let the Old Year Out

A once-common British and Irish custom involved flinging open the back door at midnight to send the old year out, then opening the front door to welcome the new one in. Some families combined it with first-footing, carefully orchestrating who would step through the front door at just the right moment. In an era of central heating and security concerns, deliberately opening all the doors at night in midwinter seems less appealing, and the ritual has largely slipped into nostalgic storytelling.

Today, it survives mainly as a charming image in memoirs and folklore books rather than something most households actually do.

Holding Hands in a Giant Ring for “Auld Lang Syne”

The song “Auld Lang Syne” is still a New Year’s staple, but the old custom of everyone joining hands in a big circle and belting out every verse is much rarer. Traditionally, people formed a ring, crossed arms, and sometimes even rushed into the center on the final line, symbolizing unity and friendship. Today the song is more likely to play quietly under fireworks or televised countdowns.

With only a few half-mumbled lines before attention shifts back to selfies and champagne, leaving the full singalong mostly to nostalgic movies and vintage party footage.

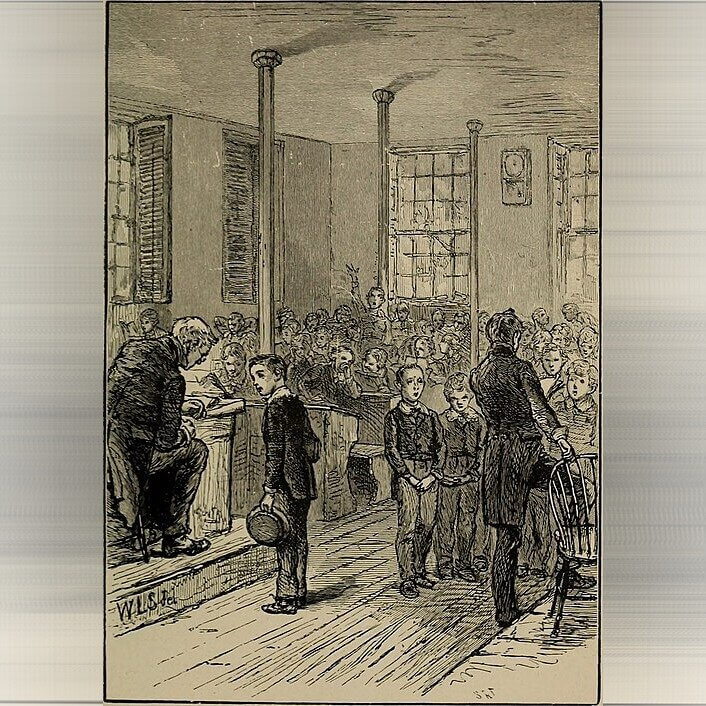

Spending Hours in a Watch Night Service Instead of Partying

Watch Night services—lengthy church gatherings on New Year’s Eve—became popular among Moravians and Methodists in the 18th century and later spread to other denominations. Worshippers spent several hours singing hymns, praying, reviewing the past year, and renewing religious covenants right up to midnight. These services offered a sober alternative to tavern revelry.

While some congregations, especially African American churches, still hold Watch Night services, the three-hour, candlelit vigils that once dominated New Year’s Eve for many believers are far less common today.

Deep-Cleaning Every Corner of the House for the New Year

In several cultures, a thorough New Year deep-clean once felt almost mandatory. Irish households scrubbed from top to bottom so they wouldn’t carry last year’s “dirt” into the new one. In China, homes were traditionally cleaned just before the Lunar New Year to sweep away bad luck—though sweeping on New Year’s Day itself was taboo. Today, busy schedules and modern cleaning habits mean fewer people dedicate a full day to symbolic scrubbing just for the calendar’s sake.

Instead, many squeeze in quick tidy-ups or rely on professional cleaners, treating the superstition as optional rather than essential.

Letting Fools and Fake Bishops Rule the Day

The medieval Feast of Fools, often held on or around January 1, turned normal society upside down. Lower clergy elected a mock bishop or “Pope of Fools,” dressed in outrageous costumes, and parodied church rituals with singing, dancing, and irreverent jokes. It was a day for role reversal and wild humor, rooted in earlier Roman Saturnalia traditions. Church authorities eventually condemned the festival as blasphemous.

The custom faded by the late Middle Ages. Today, it survives only as an inspiration for carnival scenes in novels and historical dramas.

Letting Children Roam for Coins on Hansel Monday

In Scotland and parts of Ireland, the first Monday after New Year’s Day was known as Handsel (or Hansel) Monday. Children, servants, and even postmen once expected small gifts or coins—“handsels”—from employers and householders, sometimes going door to door collecting them. In some places, a child was sent out the back door and welcomed back in the front with a coin in hand for luck.

Boxing Day customs and modern holiday schedules have mostly absorbed or replaced this quirky mini-holiday, which now survives mainly in local histories and occasional folk festivals.

Toasting Janus With Honey, Figs, and a Lost Cake

Ancient Romans marked the start of the year with feasts dedicated to Janus, the two-faced god of doorways and transitions. Celebrants offered dates, figs, honey, and a special cake—sometimes called ianual—to symbolize a sweet, prosperous year ahead. While exact recipes are lost, historians think the cake used spelt flour and was less indulgent than modern desserts.

Today, Janus lingers mostly as a metaphor for looking backward and forward at once; few people still eat his cake at midnight, preferring champagne, fireworks, and countdowns to ancient, symbolic loaves.

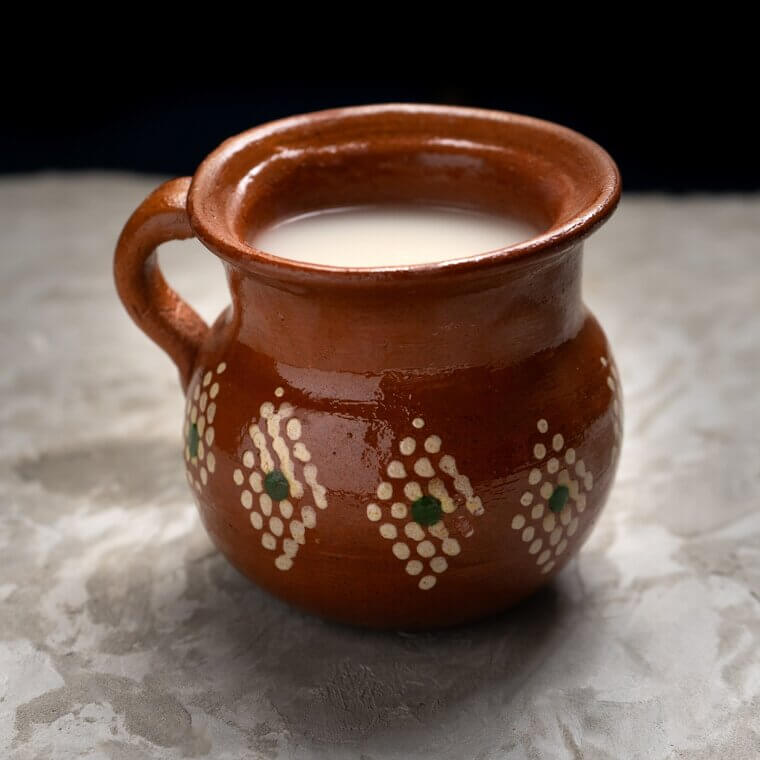

Drinking Thick Fermented Pulque Every 52 Years

For the Aztecs, the biggest “new year” moment came not annually but during the New Fire Ceremony, held every 52 years when their calendar cycle reset. After elaborate rituals, elites reportedly drank pulque, a fermented agave sap with a foamy, yogurt-like texture, as part of the celebration. The ceremony itself disappeared after the Spanish conquest, and pulque later lost ground to beer—though it’s now having a small revival in Mexico City.

As a once-in-52-years New Year drink, though, pulque’s ceremonial role is long gone, remembered more by historians and niche drinkers than everyday revelers.

Knocking Back Hot Ale-And-Whisky ‘Het Pints’

Traditional Scottish Hogmanay celebrations didn’t rely on chilled champagne. Instead, visitors might bring or receive a “hot pint” (or “het pint”): warmed mild ale seasoned with nutmeg and sometimes eggs, cut with cold ale, and fortified with whisky, carried in a kettle from house to house. Paired with dense black bun fruitcake, it was a rich, heavy combination for a freezing night.

Modern Scots are more likely to toast with neat whisky or sparkling wine, leaving the communal kettles of eggy ale to history books and the occasional heritage reenactment at folk festivals or themed pubs.

Passing Around a Communal Wassail Bowl for Luck

Medieval English households once passed a large decorated bowl of hot wassail—a mix of ale or cider, honey, spices, and sometimes eggs—from guest to guest at New Year gatherings. Everyone drank from the same vessel while exchanging the toast “Waes hael” (“be well”). Poorer families took empty bowls door to door, singing for food, drink, or coins. Over time, wassailing merged into Christmas caroling, and the communal bowl largely disappeared.

Today, hot punch is served in mugs, and health departments would probably faint at the old shared-bowl custom, however cozy it might sound in storybooks.

Reading Your Fate From a Slice of Fortune Bread

Beyond barmbrack in Ireland, versions of fortune-telling cakes appeared in several European New Year traditions. Coins, beans, or trinkets were baked into loaves; whoever found them in their slice was promised luck, marriage, or authority for the year. It was fun but occasionally tooth-endangering. Modern allergy awareness, dental worries, and pre-packaged baked goods have made hidden metal objects far less appealing.

Today, fortune cookies or written resolutions sometimes take over the “what does the year hold for me?” role instead, turning the old cake rituals into more of a nostalgic reference than a real practice.

Bribing the Kitchen God With Sticky Sweets

In traditional Chinese households, the Kitchen God was believed to report each family’s behavior to the Jade Emperor just before the Lunar New Year. To encourage a favorable review, families offered sweet foods and special candies—sometimes sugar melons—hoping his mouth would be too sticky to say anything bad. His paper image might be burned to send him skyward, then replaced after the holiday.

Today, worship of the Kitchen God has largely vanished in cities and survives only sporadically in rural areas. For many younger people, he’s more of a charming folktale figure than an actively honored household deity.

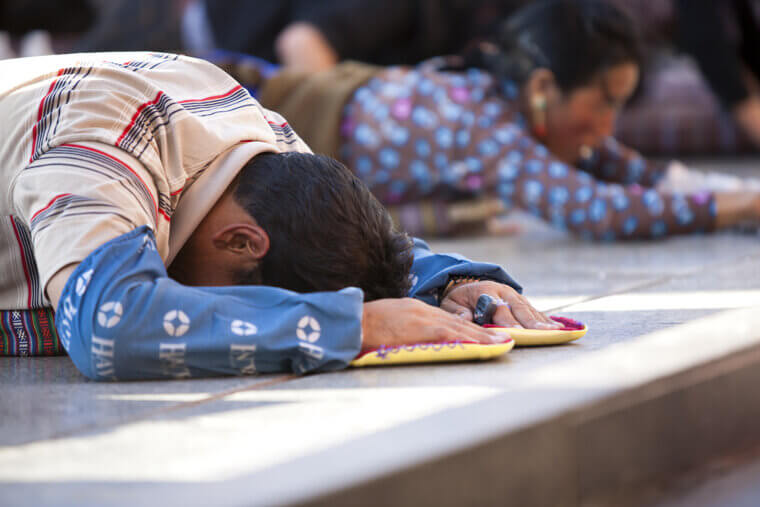

Lining Up to Kowtow to Every Elder

Another fading Chinese New Year custom involved whole families going from house to house on New Year’s Day to pay respect to elders. Younger relatives knelt and kowtowed—bowed until their heads touched the ground—before grandparents and older family members, who then handed out gifts or red envelopes. The ritual was physically demanding and deeply hierarchical.

Modern descendants often opt for simple standing bows, hugs, or video calls instead, and full formal kowtowing has mostly disappeared from everyday New Year practice, surviving mainly in historical dramas, temple ceremonies, or nostalgic family stories.

Hanging Fierce Door Gods and Peachwood Charms

Before printed couplets and generic “福” (good fortune) characters took over, many Chinese families hung detailed woodblock prints of martial “Door Gods” beside the entrance, along with peachwood charms called taofu to ward off evil during the New Year period. These were believed to physically block bad spirits from entering. Today, the handcrafted charms are hard to find, and Door God imagery has largely given way to cheaper red paper decorations.

The older protective ritual is now mostly limited to museums and collectors, or reproduced as nostalgic décor rather than serious spiritual protection.

Obeying a Long List of New Year’s Day ‘Don’t Do This’ Taboos

Chinese tradition once came with an intimidating checklist of New Year’s Day don’ts: don’t sweep, don’t wash clothes, don’t wash your hair, don’t say unlucky words, and in some regions, don’t even leave the house—so you wouldn’t “sweep away” or “wash away” good fortune. With limited holiday time and urban lifestyles, many people now ignore most of these taboos, keeping perhaps one or two for fun.

The idea of spending the first day of the year immobilized by superstition feels increasingly outdated. You’re far more likely to see a quick vacuum and a selfie than strict ritual rules.

Lighting Thousands of Handmade Lanterns Instead of Watching a Show

The Lantern Festival marks the end of the traditional Chinese New Year season. In the past, entire neighborhoods glowed with individually made paper lanterns carried by children or hung along streets, creating a sea of small lights. Modern cities often replace this with centralized, highly produced light shows or stage performances, while regulations restrict open flames.

Handmade lantern parades still exist, but the dense, low-tech forest of flickering lanterns described in older accounts has mostly drifted into memory, surviving mainly in tourist areas, historical photos, and nostalgic family stories about “how it used to look.”